Phenobarbital: The Cultural Medicine of Post-Soviet Calm

A Drug that Became a Cultural Symbol

In most of the world, phenobarbital—a classic barbiturate known for its sedative and anticonvulsant effects—has long been restricted or replaced by safer alternatives.

Yet across much of the post-Soviet region, it remains part of daily life.

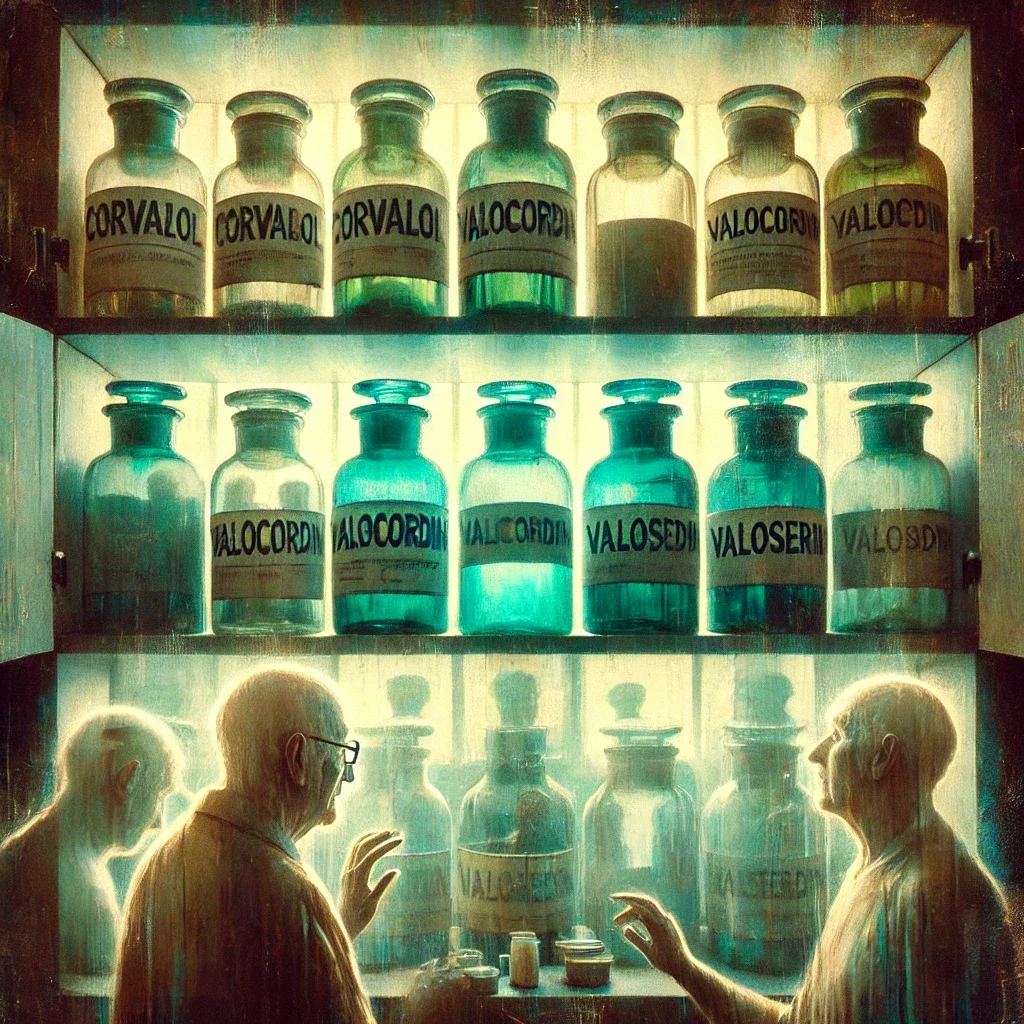

Bottles of Corvalol, Valocordin, or Valoserdin still line medicine cabinets, sold freely over the counter and used as a cure-all for anxiety, insomnia, heart “palpitations,” and stress.

This phenomenon goes far beyond pharmacology. It speaks to the psychological history, social fabric, and emotional economy of nations shaped by uncertainty and transition.

1. From War to Tradition: How It All Began

After World War II, phenobarbital became deeply woven into Soviet medicine.

It was added to “heart drops” — soothing mixtures meant to calm nerves, steady breathing, and ease chest tightness.

With limited access to psychotherapy or modern psychiatric drugs, millions turned to these brown bottles as a household remedy for peace of mind.

Even after the Soviet Union dissolved, the habit persisted.

Countries like Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan still sell Corvalol without a prescription.

In Ukraine, some forms now require one, but 25-milliliter bottles remain easy to buy.

Phenobarbital thus evolved from a medication into a symbol of stability — a comfort ritual passed down through generations.

2. The Numbers Behind the Nostalgia

Globally, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) reports that in 2022 about 364 tons of phenobarbital were produced — over a third of the world’s total for all psychotropic substances.

In Russia alone, roughly 40 million bottles of Corvalol were sold in 2023.

Even with a slight decline from the previous year, the scale is staggering.

Meanwhile, cardiovascular mortality remains extremely high across the region — nearly 940,000 deaths in Russia in 2021 — underscoring how these sedative rituals coexist with deep public-health challenges.

3. Who Uses It — and Why

The typical user is a woman over 60, often living on a modest pension, managing high blood pressure and anxiety, and lacking access to specialized care.

Studies show that people aged 65–74 are three times more likely to use phenobarbital-based medicines than younger adults.

Among those with self-diagnosed “heart problems,” more than 40% use Corvalol or similar products.

It’s also common to mix these drops with alcohol or other sedatives — a combination that can be dangerous, especially for older adults.

In many ways, this demographic pattern reflects not addiction, but adaptation: people coping with chronic stress in societies that often leave them to treat themselves.

4. The Politics of Calm

Why does this drug remain so culturally entrenched?

Several overlapping factors explain it:

Economic: It’s cheap — often 10–20 times less expensive than modern evidence-based therapy.

Medical: Many regions still face shortages of doctors and diagnostic resources.

Psychological: Decades of instability have created collective anxiety and a search for any form of relief.

Cultural: Phenobarbital has become a symbol of endurance — a trusted, old-world cure that feels safer than the bureaucracy of modern healthcare.

In short, the “Corvalol culture” is not just about medicine; it’s about coping in a post-trust society.

5. A Comforting Placebo

Pharmacologically, phenobarbital (combined with ethylbromisovalerianate) provides real but temporary sedation.

It relaxes blood vessels and reduces anxiety — but it does not treat the underlying causes of heart disease, depression, or stress.

The result is a kind of mass placebo effect: a shared illusion of control and calm in the face of systemic uncertainty.

For millions, these drops are not simply about health — they’re about emotional survival.

6. Between Medicine and Misuse

In controlled medical settings, barbiturates like phenobarbital still have legitimate uses — particularly for severe alcohol withdrawal.

Recent studies (JAMA Network Open, 2025) confirm its effectiveness when monitored carefully.

However, self-medicating withdrawal symptoms at home can lead to overdose and respiratory failure, highlighting the thin line between therapy and harm.

Conclusion: A Mirror of Society

Phenobarbital in the post-Soviet world is more than a tranquilizer.

It is a cultural artifact, a symbol of nostalgia, and a silent witness to decades of social stress, medical scarcity, and emotional fatigue.

Its enduring popularity reveals not only the pharmacology of calm but also the psychology of uncertainty — the human need to find stability in a few drops of something familiar.

As societies evolve, the challenge will be to replace those brown bottles not with prohibition, but with trust, access, and care.